How to make silence speak: the quiet insistence of Mouna Karray’s photographs

Liese Van Der WattTyburn Gallery, London 2016

“I took the road that crosses these dusty lands, an area that is lifeless yet inhabited, where the captive figure moves.” Mouna Karray, 2015

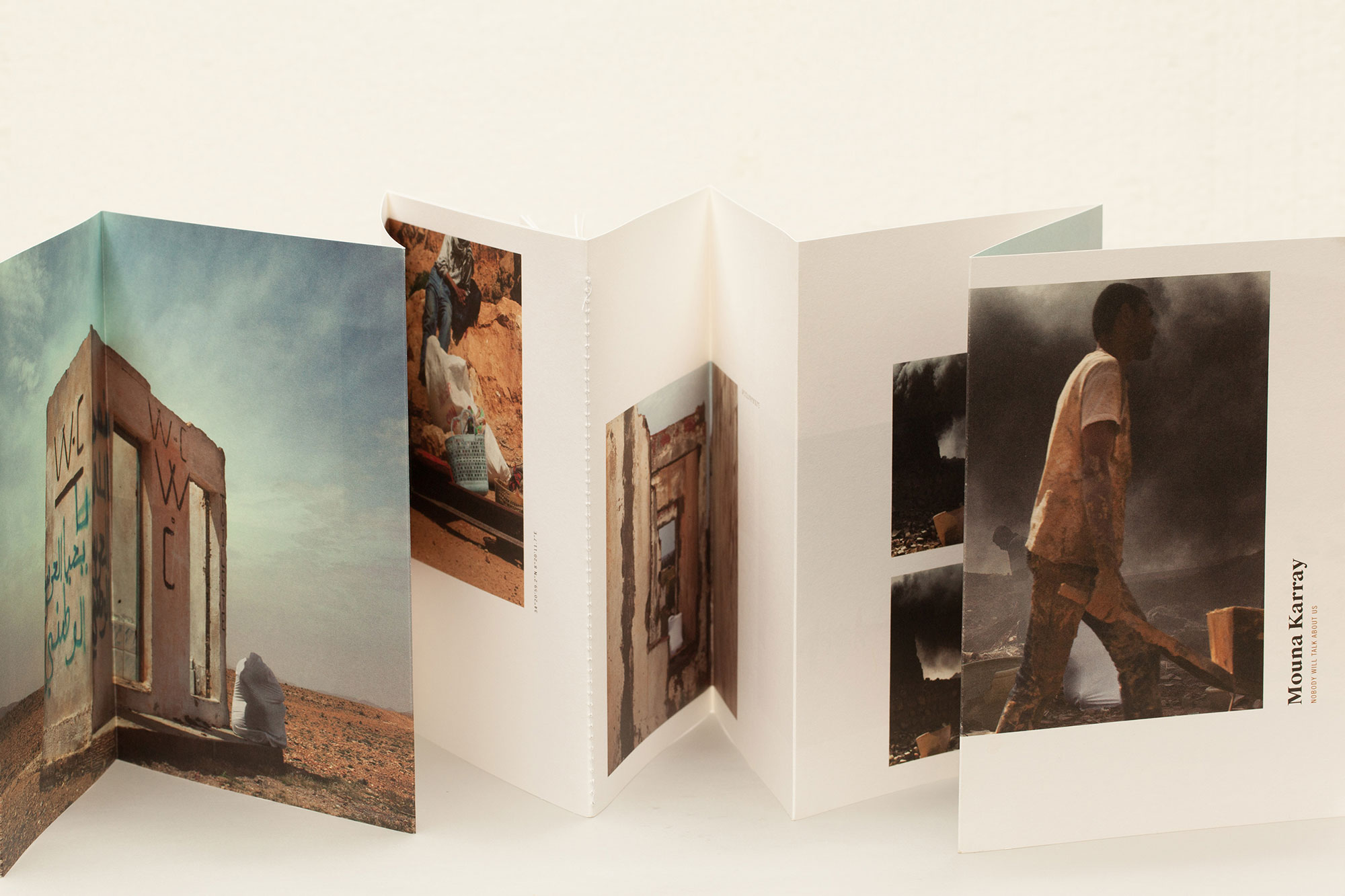

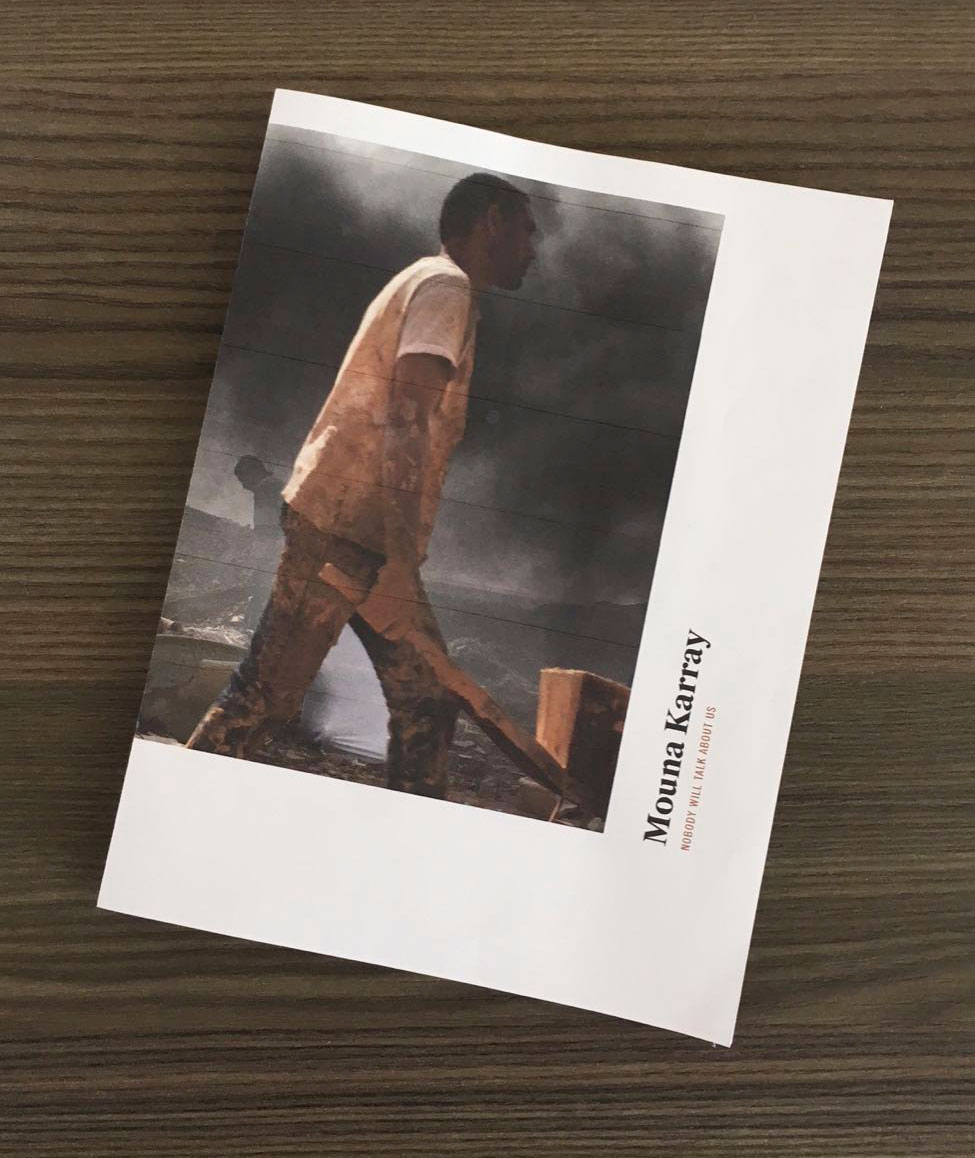

Mouna Karray’s photographs in Nobody will talk about us (2012-2015) seem to be carefully poised between the incidental and the deliberate, the random and the planned. Images of different shapes and sizes simulate a road-trip, a visual account of a journey that takes one deeper into the southwestern Tunisian desert, only to be repeatedly halted – the narrative interrupted as by punctuation, attention arrested – by the strange white object that is casually inserted into the landscape.

It is a startling sight: a white sack of sorts, containing… what exactly? A body restricted inside a bag does not quite describe this haunting image. On the one hand the captive body is clearly trying to free itself – the pressure points of struggling limbs visible under the cloth bag– but at the same time one is struck by the helplessness of it all: a bag dumped in a series of seemingly arbitrary settings.

What to make of this incongruent presence? Karray explains:

“The captive body in a white bag is a metaphor for the disinherited Tunisian south, a south forgotten by authorities since independence and overlooked up to the present day. The figure embodies the solitude, confinement and restrictions placed on these people in their difficult conditions. They exist in a silent poverty, on arid soils whose foundations were rich with minerals, which have been confiscated and stripped from these oppressed—but not submissive—souls.”

Karray relates how she visited this region in the 1990s after reading Chebika by French anthropologist Jean Duvignaud, who wrote about this tiny village in southwestern Tunisia that seemed impervious to change. Returning in 2012, she discovers a strange duality – lots of little changes have amounted to not much transformation generally. People were caught between the arrival of modern amenities such as the Internet, schools and roads, and an unchanged impoverished life, largely forgotten by the authorities and the state.

She stages a confrontation in this landscape that cannot be ignored: a body is taken – seemingly like chattel – and placed in various locations. It is an insistent presence, silently witnessing the forgotten people around it. But through its struggle and its persistent wanderings, the captive body also articulates a challenge, testifying to the lives around it and thereby forcing us to see it too, to take notice of this place and these people.

Karray is often attracted to stories that are told by unconventional means. In Murmurer (2009) she photographed abandoned walls and architectural sites around Sfax, her hometown, treating them as palimpsests that whisper of time and space. But whereas those images were largely uninhabited, in Nobody will talk about us people enter and exit the frame as they would in the snapshots that document a journey, thereby contributing to the narrative. And like Duvignaud the anthropologist, the amorphous body silently observes these chance encounters, a quiet presence in every scene. In the smoke-filled brickmaking quarry with the working men, at a makeshift petrol station, next to a road waiting for a ride, in a windswept settlement, we are made to hear this story that nobody will listen to.

As in many anthropological studies, both parties are changed by their meeting – the observed as well as the observer. Here Karray makes us, her viewers, see this landscape and these people. But they too are potentially empowered by this intervention. Asked what they think the white body-in-a-bag meant, one man answered hopefully “Maybe it’s democracy.”

It is at this point that photography is at its most powerful: when object and subject meet each other in such a way that both are potentially changed. Karray’s use of the captive body is at once a strategic way to make us notice what has hitherto been unseen, and an ongoing trope to signify engagement and the possibility of change.

Liese Van Der Watt