Murmurer Forgotten Walls or the Poetry of Urban Cicatrices

Christine BruckbauerExhibition Catalogue

Octobre 2009

(…) Don’t these black & white photographs with the auspicious title “Murmurer” (‘mur’ means wall and ‘murmurer’ whispering in French) appeal in a certain way? There is something special about them, something captivating, an enchanting spirit, a wavering of the walls, a murmuring, and a promise of hidden adventure. . (…)

MURMURER, published by Galerie El Marsa, October 2009

“Murmurer” Forgotten Walls or the Poetry of Urban Cicatrices

by Christine Bruckbauer

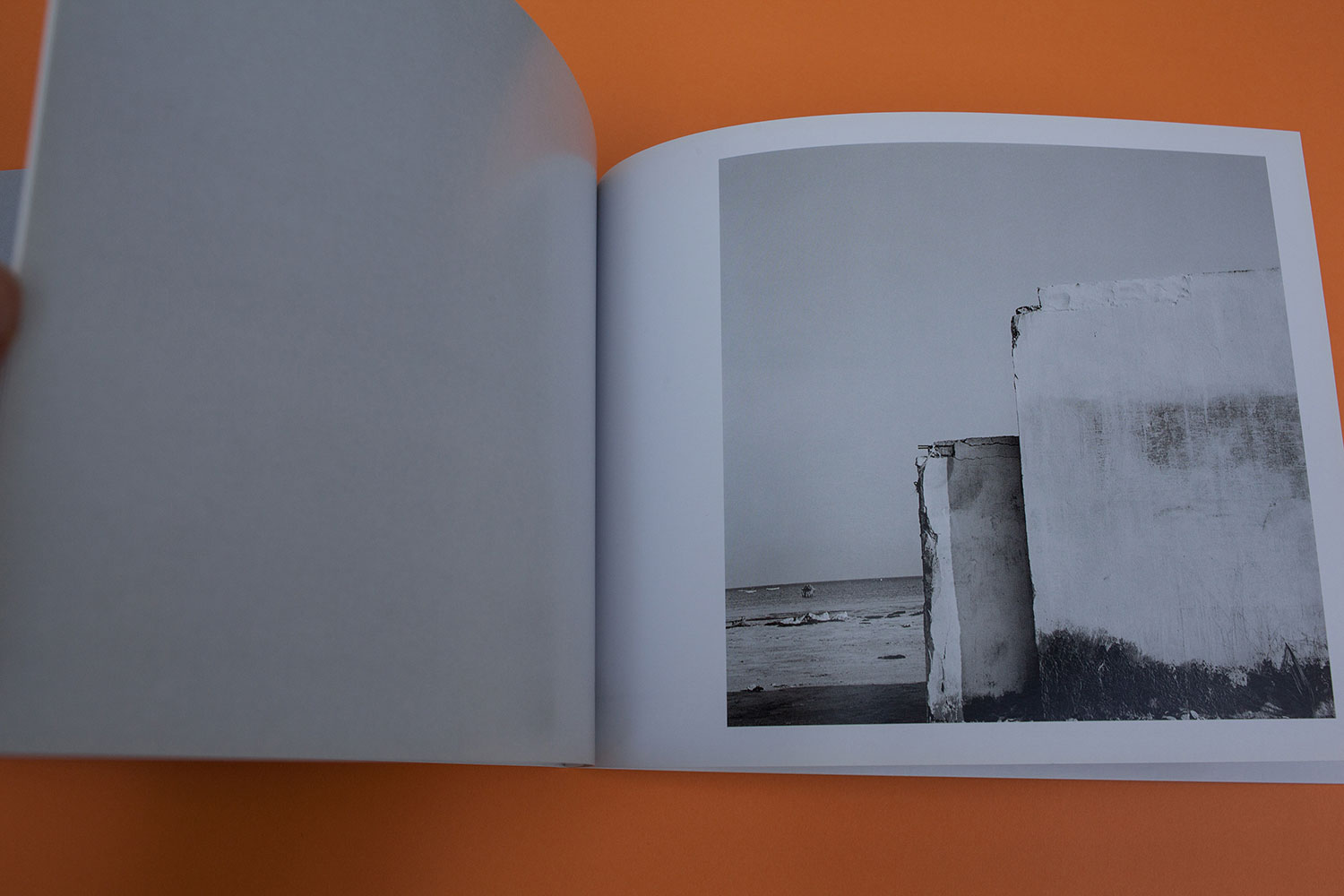

Mouna Karray photographs ‘walls’, abandoned architectural barriers, to be more precise, which continue to surface in the cityscape of Sfax, the biggest industrial town and seaport in the South of Tunisia.

In the last four decades public places in Sfax have gradually become non-accessible areas without any function. Curiously, places appear and disappear, but their borders are still standing …, the artist, who herself is a native of Sfax, describes the scenario.

Built primarily to protect and conceal, these barricades lose their credibility when decayed, dilapidated or partially demolished and remain squalid scares on the surface of the city.

But stop! Are these images really so unattractive? Don’t these black & white photographs with the auspicious title “Murmurer” (‘mur’ means wall and ‘murmurer’ whispering in French) appeal in a certain way? There is something special about them, something captivating, an enchanting spirit, a wavering of the walls, a murmuring, and a promise of hidden adventure. The mystery that lies behind these discouraging and dismissive walls extends an invitation to peep behind the partitions or even to scale them.

Alas, overcoming these ‘forests of briars’ does not lead to Sleeping Beauty dreaming of her prince and his awaking kiss.

To the contrary, the surprise is decidedly disagreeable, devastated land, debris and perhaps discarded construction machinery will be found, blatantly left behind by the former occupier.

One observes the careless treatment of nature all over the Maghreb: the countries suffer from inadequate planning policies and a lack of environmental awareness amongst their people. Sfax is more severely affected than the rest of the country due to its large chemical industry. An excessive mining of phosphogypsum has left fatal traces on the coast north of the city.

The average lifespan of a modern Tunisian house is not longer than thirty or fifty years with the general building fabric leaving much to be desired. The use of “skeleton construction”, concrete piers filled with bricks in between, leads to new builds that are not sustainable.

Instead of cleaning up, maintaining and restoring historical districts, one rather subjugates new land and focuses on projects, which guarantee medial coverage and greater prestige. For this kind of developments external financial investment is more easily generated.

Symbolic Connections

Interestingly, almost every civilisation possesses its own ‘wall’. For example: The Great Wall of China, the longest wall of the world; The Sadd-i-Iskandar, (Persian for dam or barrier of Alexander), an ancient defensive facility in north-eastern Iran; The Berlin Wall, which separated the Soviet zone of Berlin from the rest of the city between 1961 and 1989 and The Western Wall an important Jewish religious site in Jerusalem, sometimes referred to as the Wailing Wall and as al-Buraq Wall by Muslims.

Built as fortifications for protection against hostile raid in the past, raison d’être has changed over the years. Some function today as memorials of times of grief and painful separation, some are counted to the Wonders of the World and are popular tourist attractions. Others have become sacred places, like The Western Wall, where Jews come to mourn and meditate, while the Islamic tradition believes it is the place where Prophet Mohammed tied his winged steed, al-Buraq.

Ultimately, the ‘wall’ is an ambiguous term, a complex symbol, simultaneously denoting both protection and separation. It carries both positive and negative connotations dependent on the time or on which side one is located, inside or outside, before or behind. Inside, it evokes the sensations of safety and security, which can easily transform into a climate of claustrophobia or confinement. Outside, standing in front of the wall, causes an experience of exclusion and an inability to overcome the barriers.

The ‘wall’ in its virtual but also in its ‘bricks-and mortar’ configuration, plays an important role in the Arabic Islamic culture. It is best described with the Arab code ‘Haram’ (forbidden), the term relates to the ‘sanctity–reserve–restrict’ concept[1], which is manifest in architecture, dress code and behaviour.

Not much can be seen, for the view must not lead into the inner part. Something is always held from the view. The eye can only penetrate up to a certain point. It is not only the woman who is veiled in the Islamic culture, the man is also veiled, the whole civilisation is veiled, the Tunisian Filmmaker Nacer Khemir, explains the reason for the constantly distracted view.[2]

The American poet Robert Frost describes the ‘wall’ as a metaphor for the ‘myopia’ of the culture-bound.[3] Mouna Karray is concerned with her nation’s predilection of living and recalls the past glory of Arab civilisation. In her opinion this short-sightedness hems progress, like a wall obstructs the view of the open sea. There is no real perspective, no investment in the future. Like in the extensive mining of commodities which ignores the impact on the landscape and natural resources, this mentality be observed in the myopia of urban planning, reflected in numerous half-finished or abandoned buildings in the area.

Aesthetization of Wounded Walls

Mouna Karray’s photographs are documentary in nature. By portraying urban unconcern the artist explores political and social circumstances. There is no tone of accusation, instead, her photographs bear a message of resolution. The decayed condition of the walls even evokes hope, which is visualized by open doors, heavy cracks in the masonry, ripped up fences or a flight of steps.

The pure aesthetics of the black and white photography of Karray, who studied in Tunisia and Japan, softens the harsh reality and blurs the immediacy of the issue. Time seems to stand still in her pictures.

Minimalism combined with a strong, conceptual composition of horizontals and verticals makes viewing Mouna Karray’s art work a poetic experience. In one image the loosely coiled barbed wire takes on scriptorial character. Dramatic cloud formations and the desolate condition of the walls radiate melancholy and transience. Choosing the square as the leading format – also a mechanical result of her medium format camera – refers to the Muslim concept of aesthetics wherein the square is the foundation. Everything takes place in the square, the whole form, the letters (Kufic), Mekka is a square, the courtyard of a house is square.[4] A crucial step Karray’s artistic development is the curtailment of the scene. Seeing only a précis version, a detail of the whole structure, the real dimensions are lost to the viewer. Only one picture in the series provides an indication of the actual height of the wall. Herein a shadowy denizen flits by, while a spindly citrus tree casts an impressive cloud onto the massive, medieval looking wall.

It was the absurdness, the pointlessness of these architectural sites, which caught my attention. The not-knowing, what is going to happen to them? Will they be continued or will they be demolished within the nearest future? From the beginning I was fascinated by the stories the walls seem to whisper to me and by the question for their former purpose. Some of them have faced alterations with time, doors or windows were added, some of them were filled again provisionally with debris. The traces of time mark them like scars.

It is their status being a mistake, which suits me, reveals the photographer in an interview with the author.[5]

When the French theorist, Roland Barthes, questions what it was ‘per se’, that differentiates one photograph in a community of images,[6] he appoints the ‘force of attraction’ as the leading thread in his research: A photograph which I distinguish from others, which I love […] generates an inner state of excitement, a celebration, as well as labour, the pressure of the unutterable, that wants to be uttered. What else then? Interest? No, that’s not enough. Finally the term ‘adventure’ was identified as the closest term for describing the ‘force of attraction’, as the reason why one photo reaches somebody (m’advient), while the other does not. Later Barthes juxtaposes this ‘attraction’ with ‘animation’. The good photograph ‘pricks’ or ‘bruises’ the viewer, inspires and animates the thinking process: and therein lies the adventure.[7]

Looking at Mouna Karray photographs is an expedition. A quick glance upon them is not enough to appreciate the intricate composition. Exploring layer upon layer opens up a myriad of questions, some of them never to be answered.

The ‘force of attraction’ of Karray’s “Murmurer” series is not only fed by the complexity of its contents and sublime symbolism but in particular by the poetry of its black and white imagery. Karray’s sensitive photographer’s eye and her systematic and personal way of composing an image convert the blemishes into beauty.

When I love a photo, when it disturbs me, I dwell on it,[8] continues Roland Barthes in his Reflections on Photography.

By Christine Bruckbauer

[1] Fadwa El Guindi, Veil, Modesty, Privacy and Resistance, 1999, New York: Berg, 2003, 83, 84.

[2] Nacer Khemir, Le voyage à Tunis, Trigon-Film, Switzerland, 2008, Chapter 6

[3] Robert Forst, Mending Wall, poem, London: David Nutt, 1914

[4] Nacer Khemir, Chapter 7.

[5] Mouna Karray, Interview with the author, La Marsa, Tunisia, 22. October 2009

[6] Roland Barthes, Die helle Kammer: Bemerkungen zur Photographie, 1980, Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1989, 11, English translation by the author.

[7] Barthes, 28–29.

[8] Barthes, 110.